Photo is from the Ur Project of the 1920’s south of Bagdad.

People have asked many times over the years how have we managed to be able to travel and interact with people all around the world. The answer is somewhat a simple one, and here is how you can also learn for free how we began years ago. Reading allot of books prepared us for what we did, and how we came to where we are. From time to time I will add a free book for you to read here, and provide papers from John J Gentry Sr and others to advance your journey to become an international explorer.

Project Gutenberg's Journal of a Residence at Bagdad, by Anthony Groves This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Journal of a Residence at Bagdad Author: Anthony Groves Editor: Alexander Scott Release Date: August 7, 2009 [EBook #29631] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK JOURNAL OF A RESIDENCE AT BAGDAD *** Produced by Free Elf, Anne Storer and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Transcriber’s Notes:

1) Mousul/Mosul, piastre/piaster, Shiraz/Sheeraz,

Itch-Meeazin/Ech-Miazin/Etchmiazin,

each used on numerous occasions;

2) Arnaouts/Arnaoots, Dr. Beagrie/Dr. Beagry,

Beirout/Bayrout/Beyraut(x2), Saltett/Sallett,

Shanakirke/Shammakirke, Trebizond/Trebisand – once each.

All left as in original text.

JOURNAL

OF A

RESIDENCE AT BAGDAD,

&c., &c.

LONDON:

DENNETT, PRINTER, LEATHER LANE.

JOURNAL

OF A

RESIDENCE AT BAGDAD,

DURING THE YEARS 1830 AND 1831,

BY

MR. ANTHONY N. GROVES,

MISSIONARY.

LONDON:

JAMES NISBET, BERNERS STREET.

M DCCC XXXII.

INTRODUCTION.

This little work needs nothing from us to recommend it to attention. In its incidents it presents more that is keenly interesting, both to the natural and to the spiritual feelings, than it would have been easy to combine in the boldest fiction. And then it is not fiction. The manner in which the story is told leaves realities unencumbered, to produce their own impression. It might gratify the imagination, and even aid in enlarging our practical views, to consider such scenes as possible, and to fancy in what spirit a Christian might meet them; but it extends our experience, and invigorates our faith, to know that, having actually taken place, it is thus that they have been met.

The first missionaries were wont, at intervals, to return from their foreign labours, and relate to those churches whose prayers had sent them forth, “all things that God had done with them” during their absence. To the Christians at Antioch, there must have been important edification, as well as satisfaction to their affectionate concern about the individuals, and about the cause, in the narrative of Paul and Barnabas. Nor would the states of mind experienced, and the spirit manifested, by the narrators themselves be less instructive, than the various reception of their message by various hearers. In these pages, in like manner, Mr. Groves contributes to the good of the Church, an important fruit of his mission, were it to yield no other. He had cast himself upon the Lord. To Him he had left it to direct his path; to give him what things He knew he had need of, and whether outward prospects were bright or gloomy, to be the strength of his heart and his portion for ever. The publication of his former little Journal was the erection of his Eben Ezer. Hitherto, said he to us in England, the Lord hath helped me. And now, after a prolonged residence among a people with whom, in natural things, he can have no communion, and who, towards his glad tidings of salvation, are as apathetic as is compatible with the bitterest contempt; after having had, during many weeks, his individual share of the suffering, and his mind worn with the spectacle, of a city strangely visited at once with plague, and siege, and inundation, and internal tumult; widowed, and not without experience of “flesh and heart fainting and failing,” he again “blesses God for all the way he has led him,”[1] tells us that “the Lord’s great care over him in the abundant provision for all his necessities, enables him yet further to sing of his goodness;”[2] and while his situation makes him say, “what a place would this be to be alone in now” if without God, he adds, “but with Him, this is better than the garden of Eden.”[3] “The Lord is my only stay, my only support; and He is a support indeed.”[4]

It is remarkable, that at a time when the fear of pestilence has agitated the people of this country, and when the tottering fabric of society threatens to hurl down upon us as dire a confusion as that which has surrounded our brother, in a country hitherto regarded so remote from all comparison with our own; at a time when the records of the seasons at which the terrible voice of God has sounded loudest in our capital, are republished as appropriate to the contemplation of Christians at the existing crisis;[5]—this volume should have been brought before the Public, by circumstances quite unconnected with this train of God’s dealings and threatenings to our land. The Christians of Britain ought to consider, that there is a warning voice of Providence, not only in the tumults of the people, and in the terrors of the cholera around them, but even in the publication of this Journal. It is not for nothing that God has moved Mr. Groves, as it were, to an advanced post, where he might encounter the enemy before them. The alarm may have, in a measure, subsided,[6] but if the people of God are to be ever patiently waiting for the coming of their conquering King, this implies a patient preparedness for those signs of his coming, the clouds and darkness that are to go before him, in the very midst of which they must be able to lift up their heads because their redemption draweth nigh. To provide for the worst contingencies is a virtue, not a weakness, in the soldier. That Christian will not keep his garments who forgets, that in this life, he is a soldier always. No army is so orderly in peace, or so triumphant upon lesser assaults, as that which is ready always for the extremest exigencies of war.

To those who are looking for the glorious appearing of our great God and Saviour, Jesus Christ, this volume will exhibit indications of the advancement of the world towards the state in which he shall find it at his coming. The diffusion in the east of European notions and practices; the desire on the part of the rulers to possess themselves of the advantages of western intellect and skill; and on the side of the governed, the conviction of the comparative security and comfort of English domination; the vastly increased intercourse between those nations and the west, and the proposals for still further accelerating and facilitating that intercourse: all these things mark the rapid tendency, of which we have so many other signs, towards the production of one common mind throughout the human race, to issue in that combination for a common resistance of God, which, as of old, when the people were one, and had all one language, and it seemed that nothing could be restrained from them which they had imagined to do,—shall cause the Lord to come down and confound their purpose. Already has this unity of views and aims, with marvellous rapidity, prevailed in the European and American world; the press, the steam-engine by land and water, the multiplication of societies and unions, portend an advancement in it, to which nothing can set limits but the intervention of God: and now it appears that the mountain-fixedness of Asiatic prejudice and institution shall suddenly be dissolved, and absorbed into the general vortex.

And to those who may have suspected, that the prospect of the return of Jesus of Nazareth to our earth for vengeance and expurgation of evil first, and then for occupation of rule, under the face of the whole heaven, is but a speculative subject for curious minds, this little book presents matter of reflection. By circumstances of such urgent personal concernment, as those in which Mr. Groves and his departed wife have been placed, the merely speculative part of religion is put to flight. But we shall find them in the midst of confusion, and bereavement, and horror, clinging to this one hope for themselves and for the world, that the Lord cometh to reign, wherefore the earth shall be glad; deriving from this hope a delight in God, in the midst of all that seems adverse to such a sentiment, which, if it be not a proof of practical power in a doctrine, what is practical?

On some few points, Mr. Groves has given a somewhat detailed expression of his own sentiments. One of the most important of these is re-considered in the notes by the writer of this introduction. Another, on which the interest of many has already been strongly excited, is the recognition of those men as ministers of God, who do not utter the word of his truth, and who are admitted to speak without the Spirit of his truth. The question, encompassed as it has been with difficulties foreign to itself, is but a narrow one. The preaching of the Gospel is an ordinance of God. The preaching of what is not the Gospel is no ordinance of God; and affords me no opportunity of shewing my respect for divine ordinances by my attendance upon it. That men possessing the Holy Ghost should confer spiritual gifts by the laying on of hands on those who in faith receive it, is an ordinance of God: that men, not having the Holy Ghost, should lay hands on others for spiritual gifts, is no ordinance of God.

If the outward fact of what is named ordination, determines me to regard as now made of God a teacher, a pastor, an evangelist, a bishop, him who, to all intelligent and spiritual perception, is what he was, in error, and ignorance, and carnality; this is not respect for divine ordinances at all, but a faith in the opus operatum, a faith in transubstantiation transferred to men, denying the truth of my own perception, and clinging to the conclusion of my superstition, just as in the mass the senses are denied, and bread and wine visibly unaltered, are called flesh and blood. The arguments by which this notion is supported, are too complicated, and too contemptuous of unity or consistency, to be meddled with in our limited space. That Christ bade men observe what the Scribes and Pharisees taught on the authority of the law of Moses, is made a reason for reverencing what is taught on no divine authority: Scribes and Pharisees, who pretended to no divine ordination, but rested their claims on their knowledge, are made specimens of the respect due to ordination, in the case of such whose ignorance and unsound teaching are allowed. But were not the Scribes and Pharisees in many things ignorant and unsound? Yes, truly; but were these the things of which the Lord said expressly, these things observe and do? To tell us that we must observe and do what is according to Scripture, however bad the men who teach it, ordained or unordained alike; what has this to do with ordination? True, this is no excuse for those who prostitute the form and name of God’s ordinance, and know that it is prostituted: who say, “receive ye the Holy Ghost,” and would laugh as being supposed to confer the Holy Ghost: but there is no necessity for running from this crime, to the error of which we have spoken. Let us acknowledge our wretchedness, and misery, and poverty, and blindness, and nakedness. When the laws were transgressed, and the everlasting covenant broken; then the ordinance was changed, as Isaiah foretold it should,[7] among the causes why the earth is defiled under the inhabitants thereof.

The Apostolic Epistles contain little, if any thing, to establish the pastoral authority in a single person of each church or congregation: and the omission of all allusion to such an office is often very remarkable from the occasion seeming to assure us, that it would have been mentioned had it existed. The Epistles of the Lord to the seven churches are therefore resorted to for proof of the existence and nature of the place of a single pastor with peculiar and exclusive powers. But neither there nor elsewhere is the fact of ordination once referred to, in relation to the receiving or rejection of those who claimed to speak in the name of Christ. In these very Epistles there is a commendation for disregarding for the truth’s sake the highest titles of ecclesiastical office. “Thou canst not bear them which are evil: thou hast tried them which say they are apostles, and are not, and hast found them liars.”[8] I believe, “not to bear them which are evil” pastors, evangelists or apostles, is as commendable in England as in Ephesus in the eye of the Head of the Churches. Is there a syllable in the Bible to lead us to suppose that these liars were detected by any other means than those which Paul had already taught the Church? “Though we, or an angel from heaven, preach any other gospel unto you than that which we have preached unto you, let him be accursed.” As for the ordinance, such passages as Titus i. 9, make selection a part of that ordinance: the bishop is to be one “holding fast the word of truth as he hath been taught.” Now, on what authority shall this part of the ordinance, viz. selection, be omitted, and no flaw follow: while the presence or omission of a manual act in certain hands is to constitute the reality or absence of Divine ordination?

A. J. SCOTT.

Woolwich, Aug. 16th, 1832.

JOURNAL

OF A

RESIDENCE AT BAGDAD.

Bagdad, April 2, 1830.

We begin to find that our school-room is not large enough to contain the children, and we have been obliged therefore to add to it another. We have now fifty-eight boys and nine girls, and might have many more girls had we the means for instructing them; but we have as yet no other help than the schoolmaster’s wife, who knows very little of any thing, and therefore is very unfit to bring those into order who have been educated without any order. But I have no doubt of the Lord’s sending us, in due time, sufficient help of all kinds.

April 3.—An Armenian merchant from Egypt and Syria, was with us to-day; a Roman Catholic by profession, but an infidel in fact. He said it was all one to him, whether men were Armenian, Syrian, Mohammedan, or Jew, so that they were good. He had left Beirout about two months, and said there were none of the missionaries there then; but that he knew there the Armenian Catholic bishop, and an Armenian priest, who had left the Roman Catholic church, and who were in Lebanon—he said they were friends of his, and very good men. We feel interested in receiving some missionary intelligence, to know whether or not Syria is still deserted.

We have received from Shushee a parcel of our Lord’s Sermon on the Mount, in the vulgar Armenian. We were very much rejoiced at this, as it enabled us to supersede, in some little degree, the old language; but in determining that every boy sufficiently advanced, should learn a verse a day, we met with some opposition from two or three of the elder boys, and I think two will leave the school in consequence; but the Lord will easily enable us to triumph over all; of this I have no doubt, at all events I see my way clear come what will. Captain Strong has taken a letter for me to Archdeacon Parr, to ask for some school materials, such as slates and slate pencils for the school. I feel daily more established in the conviction, that our Lord has led us to this place, and that he will make our way apparent, as we go on in faithful waiting upon him.

I cannot sufficiently thank God for sending my dear brother Pfander with me, for had it not been for him, I could not have attempted any thing, so that all that has now been done, must rather be considered his than mine, as I have only been able to look on and approve. But if the Lord’s work is advanced, I can praise him by whomsoever it may be promoted.

June 12.—The circumstances of our situation are now going on so regularly, that there is little to write about, more than that the Lord’s mercies are new every morning. Since Captain Strong left us, there has arrived here a Mr. and Mrs. Mignan, and another gentleman, named Elliot, neither of whom seem to know, at present, whether they will remain here or go on.

The capidji or officer, who came from Constantinople, bringing a firman to the Pasha, is desired to take back with him a drawing of one of the soldiers whom Major T. is organizing for the Pasha. Major T.’s son is just arrived from India, and he also is going to organize a body of horse; in fact, every thing is tending to the establishment of an European influence, and it may be the Lord’s pleasure thus to prepare the way for his servants to publish the tidings which the sheep will hear. This tendency to adopt European manners and improvements, is not only manifested in the military department, but in others more important. The Pasha has a great desire to introduce steam navigation on these two beautiful rivers. A proposal has been made from an agent of the Bristol Steam Company, to the Pasha, through Major T., to have a steam vessel in the first place between Bussorah and this place; and secondly, if possible, to extend the navigation, either by the old canal or by a new one, into the Euphrates and up to Beer. This navigation will bring one within three days of the Mediterranean,[9] without the fatigue, danger, and loss of time to which travellers are exposed in the present journey. It will be a most important opening for missionaries; for should this mode of conveyance once get established, the route by Constantinople would almost cease, and some arrangement would soon be made for going from Scanderoon to the different important stations in the Mediterranean.

There is a gentleman here on his return to England, a Mr. Bywater, whom Mr. Taylor wishes to undertake a survey of the Euphrates, from Beer to the canal, which connects it with this place. Till within about twenty years, heavy artillery came to this place by that river, so there can be but little doubt that a steam packet would be able to go; though it might not be of the same size as the one between this and Bussorah. The voyage between these places backwards and forwards, it is proposed to do in eight days, which now takes about six or seven weeks, and during the whole of the returning voyage, which is long, being against the current, you are at present exposed to the attacks of the Arabs every hour, whereas the steam packet would have nothing to fear from them. In fact, I feel the Lord is preparing great changes in the heart of this nation, or rather from one end of it to the other; and the events which have taken place in that part of the empire around Constantinople, have tended to the hastening on of these changes.

Among the boys that come to me to learn English, I have one, the son of a rich Roman Catholic jeweller of this place. So important is the commercial relation between this place and India become, that the number who wish to learn English of me, is much greater than I can possibly take charge of, as this is not with me a primary object; but it is a most important field of labour, and one that might have, I think, very interesting results, for they will bear opposition to their own views more easily in another language than in their own: it does not come to them like a book written to oppose them, and thus truth may slide gently in. My Moolah, who is teaching me Arabic, and whose son I teach English, told me, that in two or three years he would send his son to England to complete his knowledge of English. Now to those who know nothing of the Turks, this may not appear remarkable, but to those who do, it will exhibit a striking breaking down of prejudice in this individual.

There is a famous man here, a Mohammedan by profession, but in reality an infidel, who is the head of a pantheistic sect, who believe God to be every thing and every thing to be God, so that he readily admits, on this notion, the divinity of our blessed Lord. Infidelity is extending on every side in these countries. My Moolah said, that now a-days, if you asked a Christian whether he were a Christian, he would say, Yes; but if you asked him who Christ was, or why he was attached to him, he did not know. And in the same manner he said, if you asked a Mohammedan a similar question, he would also say, he did not know, but that he went as others went; but, he added, now all the Sultans were sending out men to teach, the Sultan of England—the Sultan of Stamboul, &c. By this I imagine his impression is, that we are sent out by the king of England.

Our school is, on the whole, going on very well. We have introduced classes, and a general table of good and bad behaviour, of lessons, of absence, and of attendance; and they all go on, learning a portion of Scripture every day in the vulgar dialect. This is something.

I am beginning to feel my acquaintance with Arabic increase under the plan which I am now pursuing with the boys who learn English. They bring me Arabic phrases, and as far as my knowledge extends, I give them the meaning in English; and when that fails, I write it down for inquiry from the Moolah next day, and then by asking words in Arabic every day for the boys to give me the English, I at last get the expressions so impressed on my memory, that when I want them they arise almost without thought. Another advantage from the boys bringing phrases and words, is that they bring such as they use in the spoken Arabic, which is very different from the written. This is a plan I would recommend, whenever it can be adopted, to every missionary; for there is a stimulus to the memory in having the questions to ask every day, and having only the English written down, which nothing else gives.

We have lately had a little proof of Turkish honesty. The man who sells us wood, charged us seven tagar, and brought us somewhat less than three.

Our souls are much refreshed by the contemplation of our Lord’s coming to complete the mystery of godliness. Oh, how long shall it be, ere he be admired in all them that believe.

June 26.—We have heard to-day from Mrs. G.’s brother J. from Alexander Casan Beg, mentioned in a preceding part of my journal, and from Mr. Glen. All our various accounts were welcome. Some of the information contained in them enables us to rejoice in those we love naturally, some in those we love spiritually.

In the letters of Alexander C. Beg, and Mr. Glen, I have received the intelligence that the former would not now be able to join us, as he had previously received an offer from the Scottish Missionary Society, to become a missionary of theirs in India; for certain reasons, however, he does not at present seem able to accept it. Concerning this Mohammedan convert, it is impossible not to feel the deepest interest.

We have just had some interesting conversation with a poor Jacobite, who is come from Merdin, with a letter from his matran or bishop, about two churches which the Roman Catholics have taken away from the Jacobites. His description of their state is striking. He says, the Pasha of Merdin cares neither for this Pasha, who is his immediate superior, nor for the Sultan; and that he encourages these disputes among the Christians, that he may get money from both parties, who bribe him by turns. He says, that the Yezidees, when they see a Syrian priest coming, will get off their horse and salute him, and kiss his hand, and that the Kourds are a much worse people than they, but that Roman Catholics are worse than either.—I was surprised to find that the Roman Catholic bishop has a school of fifty girls learning to read Arabic, and to work at their needle.

We have heard to-day that the Mohammedans, inhabitants of the town, are much dissatisfied with the Sultan and with the Pasha, for introducing European customs. They say, they are already Christians, and one of them asked Mr. Swoboda, if it was true that the old missid or mosque near us, was to become again a Christian church, and whether the beating of the drums every evening after the European manner at the seroy or palace, did not mean that the Pasha was becoming a Christian. And they say, that the military uniforms now introducing, are haram or unlawful. Major T. has induced the Pasha to have a regiment dressed completely in the European fashion, and is now forming some horse regiments on the same plan. All these things will clearly tend to one of these two results—either to the overthrow of Mohammedanism by the introduction of European manners and intelligence, or to a tremendous crisis in endeavouring to throw off the burden which the great mass of the lower and bigoted Mohammedans abhor. But still the Lord knows, and has given his angels charge to seal his elect before these things come to pass.

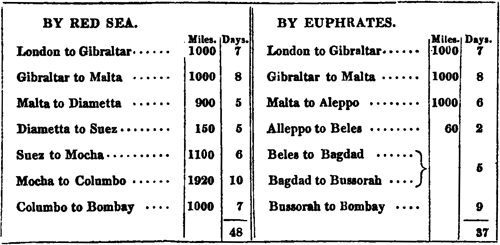

Our attention has again been directed to the subject of steam navigation between Bombay and England, by the arrival of Mr. James Taylor from Bombay. This gentleman has been engaged for some time in undertaking to effect steam communication by the Red Sea: with the view of making final arrangements on the subject he had just been to Bombay, and wished to have returned by the Red Sea, but difficulties arising, he determined to come by way of the Persian Gulf and this city, and to cross the desert. On his arrival here, he was made acquainted with the previous plans for steam navigation on these rivers; and he quickly perceived that if the river were navigable, and no other difficulties arose, the preference must be given to this route, as being at least ten days shorter to Bombay, and of the thirty or thirty-five days which remained, seven, or perhaps five, would be spent on two beautiful rivers, with opportunities of obtaining from its banks vegetables and fruits; and instead of the Red Sea, which is rocky, stormy, and little known, there would be the Persian Gulf, which has been surveyed in every part, and is peculiarly free from storms. From the mouth of the Persian Gulf, the boat would go direct to Bombay instead of going down to Columbo from the mouth of the Red Sea, and then up the western side of the Peninsula of India. In Egypt also they would have five days journey over the desert, whilst from Aleppo they would only have two to a place on the Euphrates, called Beer. Fuel also in abundance might be obtained here, either from wood or bitumen; in fact, Mr. Taylor feels that if it can be accomplished, it would save expense on the voyage. The only two difficulties that oppose themselves to this route are, first, the Arabs, and secondly, whether there be a sufficiency of water in the rivers. As to the Arabs, a steamer has nothing to fear, for by keeping mid-stream at the rate they go, no Arab would touch them or attempt to do it. The present vessels they have no power over in going down, but when they are dragged up by Arab trackers, then they are easily attacked. As to the second objection, the want of water, there appears no insurmountable difficulty here, as all the heavy ordnance from Constantinople were brought down the Euphrates from Beer, on rafts, or, as they are called, kelecks; these, independent of their width, being greater than that of a steamer, actually draw more water when heavily laden. There does not appear to be more than one place where there is a doubt, and that is at El Dar, the ancient Thapsacus, where we understand at one season, when the waters are at the lowest point, a camel can hardly go over; but still, perhaps, further information may be desirable. The Pasha has entered very heartily into this plan, and offered either to clear out an old canal, or to cut a new one between this river and the Euphrates. The mouth of the Euphrates is one extended marsh, which forms the best rice-grounds of the country. The distance between the two rivers at this place is about thirty miles. Mr. James Taylor thinks that travellers may reach England from this in twenty-three days, and Bombay in twelve: should this ever take place, steam boats will be passing twice a month up and down this river with passengers from India and England; the effects of such a change, both moral, spiritual, and political, none can tell, but that they must be great every one may see.

I have been this morning talking with my Moolah about the two rivers, as to their capability of steam navigation. He decidedly gives the preference to the Euphrates, and says, that the average depth is the height of two men, or ten feet—even till considerably above Beer; but that the Tigris, above Mousul, is very shallow.[10]

This possibility thus set before us of seeing those we love, and many of the Lord’s dear servants here, is most comforting and encouraging: this place would become a frontier post of Christian labour, from which we might daily hope to send forth labourers to China, India, and elsewhere, and the work of publishing the testimony of Jesus be accomplished before the Lord come. However, we are in the Lord’s hands, and he will bring to pass what concerns his own honour, and we will wait and see: a much greater opening has taken place since we came here than we could have hoped for, and much more will yet open upon us than we can now foresee. Things cannot remain as they are, whether they continue to advance as they are now doing, or whether bigotry be allowed to make a last vain effort to regain her ancient position; still some decided change must be the final result of the present state of things.

From the Bible Society at Bombay, I have received accounts of their having sent me two English Bibles, fifty Testaments, twenty Arabic Bibles, fifty Syriac Gospels, fifty Syriac Testaments, fifty Armenian Bibles, one hundred Persian Psalters, seventy-five Persian Genesis, and six Hebrew Testaments. In this are omitted those which are most important to us, the Chaldean, the Persian, and the Arabic Testament; but perhaps when they receive a supply from the Parent Society, they will then forward these likewise.

I have also received a letter from Severndroog, from the first tutor of my little boys, Mr. N., a true and dear person in the Lord, and he mentions that they had, since he last wrote, admitted to their church, four Hindoos and two Roman Catholics, and that one Hindoo still remains, whom they hope soon to admit.

The following is the estimate of the time which the voyages, by the Red Sea, and by these rivers to India, would respectively occupy:

I have recently had some conversation with Mr. J. Taylor, who is waiting only to see the Pasha to make final arrangements.

Another very important feature of the above plan for steam communication with India is, that those societies who have missionaries there, may send out their secretaries to encourage and counsel them, by which means they will be able not only to enter more fully into the feelings and circumstances of those they send, but will be able to make their own reports, which will be more agreeable to those engaged in the work—to tell about which must always be a difficult undertaking.

I found yesterday that one of the gentlemen who came hither lately from India, was a Mr. Hull, the son of Mrs. Hull, of Marpool, near Exmouth, who, however, is not going across the desert, but round by Mosul and Merdin, to Stamboul. He hopes to be home in September.

Mr. Pfander learnt from some Armenians yesterday, that they were much pleased with the children learning the Scriptures in the vulgar dialect; that they were so far able to understand the ancient language still read in their churches, and they expressed a wish that they might have a complete translation in the vulgar tongue. Those Bibles we now have from the Bible Society, are in the dialect of Constantinople, which is by no means generally or well understood here, where the Erivan dialect prevails, which they use in the Karabagh, in the north of Persia, and in all these countries. The missionaries at Shushee are going on with the New Testament: Mr. Dittrich has finished the translation of the four Gospels, and we hope it will be printed for the Bible Society this year, for we greatly need Armenian books in the vulgar dialect, by which we may, step by step, supersede the old altogether. We also greatly want Arabic school-books; but these we shall hope to get from Malta, through the labours of Mr. Jowett.

We find the general feeling here, not only among Christians, but even among the Mohammedans, is a wish that the English power might prevail here, for although the Pasha does not directly tax them high, yet from a bunch of grapes to a barrel of gunpowder, he has the skimming of the cream, and leaves the milk to his subjects to do with as they can. Once a month at least the money is changed. When the Pasha has a great deal of a certain base money that he issues, he fixes the price higher by certain degrees, on pain of mutilation, and when he has paid it all away, or has any great sums to receive, he lowers the value by as many degrees as he has raised it before. And hearing, as they universally do now, of our government in India, that it is mild and equitable, most of them would gladly exchange their present condition, and be subject to the British government. This conduct on the part of the Pasha, begets an universal system of smuggling and fraud among all classes, so that the state of these people is indeed very, very bad. I never felt more powerfully than now, the joy of having nothing to do with these things; so that let men govern as they will, I feel my path is to live in subjection to the powers that be, and to exhort others to the same, even though it be such oppressive despotism as this. We have to shew them by this, that our kingdom is not of this world, and that these are not things about which we contend. But our life being hid where no storms can assail, “with Christ in God”—and our wealth being where no moth or rust doth corrupt, we leave those who are of this world to manage its concerns as they list, and we submit to them in every thing as far as a good conscience will admit.

July 12.—We have heard of two Jews, who have bought two Hebrew New Testaments, and a very respectable Jewish banker has been here to see Mr. Pfander, with the German Jew, whom I have mentioned before, and who is still desirous of leaving the broad road, without heart to trust in him who is in the heavenly path, the way, the truth, and the life. He is now here, endeavouring to obtain a livelihood by teaching a few boys Hebrew, and comes to read the book of Job in German with Mr. Pfander, without any of their explanations, one of which, as it regards Job, is as follows. They say that every individual of the human race actually existed in Adam, some in his nails, some in his toes, some in his eyes, mouth, &c. &c., and they think, in proportion to the proximity of the position of any person to the parts concerned in eating and digesting the forbidden fruit, will be their degree of guilt and measure of punishment here; so they consider that Job had his place near the mouth. Such are the follies which now occupy the minds of this interesting people, instead of the Lord of life and glory.

Colonization appears to have entered into the contemplation of those engaged in steam-navigation, and the planting of indigo and sugar. To this end, the Pasha has granted them thirty miles of land on the banks of the river. Just before Mr. Taylor was to set off to go through the desert, news came that the Arab tribes on the road were at war among themselves, and that it would therefore not be safe for him to go that way, so he changed his route, and went on the 13th, by the way of Mousul and Merdin, nearly double the distance, and at the same time, Mr. Bywater and Mr. Elliot set off to Beer, from whence they intend going down the Euphrates and examining that river as far down as Babylon.

The old Jew, who came with the German, heartily entered into some conversation about the coming of Christ. A school of Jewish children might, I think, easily be obtained here, if you would teach them English and the Old Testament only.

Our Moolah has mentioned, that he has been reading the New Testament with another Moolah, who wishes to have a copy of Sabat’s translation, thinking that that might stimulate them to answer it; but that the Propaganda edition is so vulgar, it offends them, for like the Greeks they seek after wisdom. Still, if they read, the testimony of God is delivered, and the plucking a few brands from the general conflagration, is the great work till the Lord come. They have a most proud and obstinate hatred against the name of Jesus, before whom all must bow.

We have been interested by some inquiries made by our schoolmaster and his father, relative to our morning and evening prayers; he wanted to know what they were, and Mr. Pfander had the greatest difficulty in making him understand, that we prayed from a sense of our present wants. They said, they had heard from their books, that in the time of the apostles men were without form of prayer, and were enabled to pray from their hearts; but that it was not so now. They also asked some questions about the Lord’s Supper, whether we used wine mixed with water or unmixed; bread leavened or unleavened. They seem anxious to know more, and may the Lord give an open door to them!

We cannot help feeling, that the difficulties among the Mohammedans, and apostate Christian churches are great beyond any thing that can be imagined previous to experience. The difficulties of absolute falsehood are as nothing to those of perverted truth, as we see in the confounding infant baptism with the renewing of the Holy Ghost. In every thing it is the same, prayer, praise, love, all is perverted, and yet the name retained. The communications we received from Mr. G——l and others,[11] about the state of Christianity in these countries, is but too true, and what he states about the monks at Itch-Meeazin may be doubtless true; at least I suppose it is the seat of the Armenian Patriarch he means, for I know of no other Armenian church in these parts, where this service is kept up of reading the whole Book of Psalms every day. The office of a missionary in these countries is, to live the Gospel before them in the power of the Holy Ghost, and to drop like the dew, line upon line, and precept upon precept, here a little and there a little, till God give the increase of his labours; but it must be by patient continuance in well doing against every discouraging circumstance, from the remembrance of what we ourselves once were.

We have this day heard, that the cholera or the plague is at Tabreez, and that they are dying 4 or 5,000 a day; but this, I have no doubt, is a gross exaggeration. May the Lord watch over the seed that seems sowing there, and make the judgments that are in the earth warnings to men to return to God. We also have the cholera here; but I trust not severely.

The last Tartar who took our letters with the head of the ex-Khiahya was plundered, so that our letters were lost which we sent by him.

We have been to-day in hopes of obtaining another Moolah, for teaching the children in the school to read and write Arabic. For two months we have been trying, without success, to obtain one, so great is their prejudice against teaching Christians at all, but especially themselves to read the New Testament; but as our Lord does every thing for us, we doubt not he will do this also if it be best.

I am much led to think on those of my dear missionary brethren, who look for the kingdom of Christ to come in by a gradual extension of the exertions now making. This view seems to me very discouraging; for surely after labouring for years, and so little having been done, we may all naturally be led to doubt if we are in our places; but to those who feel their place to be to preach Jesus, and publish the Testament in his blood, whether men will hear or whether they will forbear, they have nothing to discourage them, knowing they are a sweet savour of Christ. I daily feel more and more, that till the Lord come our service will be chiefly to gather out the few grapes that belong to the Lord’s vine, and publish his testimony in all nations; there may be here and there a fruitful field on some pleasant hill, but as a whole, the cry will be, “Who hath believed our report, and to whom is the arm of the Lord revealed.”

It is the constant practice here among the Jews, when they hear our blessed Lord’s name mentioned, or mention it themselves, to curse him; so awful is their present state of opposition, Mohammedans will not hear, and Christians do not care for any of those things—such is the present state here; but if the Lord prosper our labour, we shall see what the end will be, when the Almighty word of God becomes understood. The poor German Jew still holds on; he has too much honesty to live by writing lying amulets, and too little faith to cast himself on the Lord; but his constant cry is, What shall I do to live? The insight he gives us into the state of the Jews here is most awful, but notwithstanding, there appears to me a most abundant field of labour among the 10,000 who are here. Yesterday he called me suddenly while at breakfast, to see a poor young Jewess who had been married but two months, and had fallen over the bridge with her little brother in her arms. The scene was awfully interesting. Not less perhaps than 300 Jews, with their wives, were in the house, but tumultuous as the waves of the sea, without hope and without God in the world. There was no hope of recovering her. She had been in the water an hour and a half, and had there been life, they were acting so as to extinguish every spark. She was lying in a close room crowded to suffocation, with the windows shut; and they were burning under her nose charcoal and wool.

The Armenian boys, who are learning English, go on with great zeal, and may in the course of time become very interesting.

We have at length received information, that all our things are arrived at Bussorah, and among the rest, the lithographic press, which we hope to find most useful to us in our present position; every thing happens rightly and well; they have been delayed for some time in coming up the river, in consequence of a quarrel between the Pasha and the Arab tribe, the Beni-Laam, in consequence of the plunder of Dr. Beaky’s boat, but we expect it will be settled, as the Pasha has acceded to the terms the Sheikh offered, and has sent him down a dress of honour.

I am sometimes led, in contemplating the gentlemanly and imposing aspect which our present missionary institutions bear, and contrasting them with the early days of the church, when apostolic fishermen and tent-makers published the testimony, to think that much will not be done till we go back again to primitive principles, and let the nameless poor, and their unrecorded and unsung labours be those on which our hopes, under God, are fixed.

We have just heard an interesting case. The gardener of the Pasha is a Greek, who was lately sent to him at his request from Constantinople, and yesterday (August 6), he became a Mohammedan. He had two daughters of thirteen and fourteen, whom he also wished to become Mohammedans; but they would not consent, and ran away to the factory, where they might have remained under English protection; but they would not stay, unless their brother, and his wife, and their servants could remain with them; so they left, as Major T—— had not room for them all, having already the family of one of the servants of the Pasha, who is imprisoned for some delinquency in connection with the revenue accruing to the Pasha from the bazaar.

There has been with Mr. Pfander to-day one of the writers of the Pasha, and he read some parts of the Turkish New Testament, which he very well understood, and expressed much pleasure in the reading of; but when, on his being about to leave, Mr. P. asked him to accept of a Turkish Testament, he very politely declined it.

There is another person come from Merdin, with the view of settling the affair between the Syrians and the Roman Catholics at Merdin. He is a weaver of Diarbekr; and from him Mr. Pfander learns, that in the last census taken by the Pasha, the Syrians were 700 families, and the Armenians 6,700: this certainly opens a most interesting field for Christian inquiry: he also said, that the Syrians in the mountains were perfectly independent of the Mohammedans, and among themselves are divided into little clans under their respective Bishops. He also stated, that reading and writing were much more cultivated among the independent Syrians than those in the plains.

He also said there would be no difficulty whatever in going among the Yezidees with a Syrian guide. The language which the independent Syrians speak is Syriac, which is near the ancient Syriac, and that they understand fully the Syrian Scriptures when read in their churches. We hope, therefore, should the Lord spare our lives, to have an opportunity of circulating some of the many copies of the Scriptures in Syriac, which Mr. Pfander has brought from Shushee, and some that I expect will come from Bombay for me.

The Gerba tribe of Arabs are come almost close to Bagdad, to check whom the Pasha intends sending out the troops that have been under the discipline of the English.

We have also heard from the Syrian, that from Mousul to Mardin the road by the mountains of Sinjar is safer than by the plains. Among the Yezidees and Syrians, no Mohammedan lives. It is impossible to consider such an immense Christian population as that in Diarbekr, without feeling a wish to pour in upon it the fountains of living waters, which we are so abundantly blessed with. Oh, that some one would come out, and settle down in such a place as Diarbekr—what an abundant field of labour!

August 14.—A young Jew was here to-day, and bought three Arabic Bibles of Mr. Pfander, at 25 piastres of this place each, i.e. about 5s. sterling. This is almost the beginning. Many might perhaps have been given away; but as we find that those of Mr. Wolff were generally burnt, we wish them to buy them, at least, at such a price that they would not burn them. He took away a Hebrew New Testament, but returned it again. I should feel deeply interested in some one coming to take charge of a Jewish school, in which the Old Testament, Hebrew, and Arabic, might be the basis of instruction. I make no doubt, that at once a most interesting school might be established here on a very large scale, for they have but one school of about 150 poor boys at their synagogue, or rather synagogues, for they have six, but all in one place, and forming one building; they have also three rabbies, and besides the boys which are taught at the above school, many others are educated at home by teachers. Now, nothing can be more distinct than their wish for a school, and their promise of supporting it on the basis of the Old Testament being taught as a school-book, which certainly, as a primary step, is a most important one to cause them, by the Lord’s blessing, to see that the book which they now disfigure by monstrous interpretations, has yet in itself, by the illumination of God’s Spirit, a clear, simple, and, in all essential points, an intelligible meaning, without the aid of man’s exposition. But should they finally turn round and oppose the school, which as soon as the power of it is felt, they most assuredly would do, still some might remain, and if none should, there is still a most abundant field of labour in circulating the Scriptures, and in conversation among them in this city, and throughout Mesopotamia, where they abound in almost every town.

We have heard from a Jew, that Sakies, the Armenian Agent of the East India Company, had given the Jews directions to treat Mr. Wolff when here with attention, and to invite him to their houses. The Jews here are closely connected with the English, at least many of them, who are under English protection.

August 15. Sunday.—The thermometer this day has been the highest hitherto for the year, 117 in the shade, and 155 in the sun.[12] This is the time when the dates ripen, and the most oppressive in the year; but by the Lord’s great mercy, we are all in health and strength, though sometimes we feel a little disposed to think it is so hot, that we may be excused from doing any thing; but my English scholars keep me employed six hours a day, which prevents me from thinking much about the heat, though not from feeling it. I can truly say, it is far more tolerable than I expected, and yet there are few places on the face of the earth hotter. The temperature of India is not near so high; and I question, if there is any place, that for the year through would average so high.

August 17.—The Jew has been here, and bought another Arabic Bible. I showed him one of the Hebrew Psalters of the Jews’ Society. He greatly desired to have it; but I could not spare that; but promised him that when mine came up from Bussorah, I would let him know.

We have this day a new Moolah, the best we could get, but not altogether such as we could have desired.

The Jews here cannot believe that Christians know any thing of Hebrew, and are therefore surprised to see Hebrew books with us. Oh, should the Lord allow us to be of any use to this holy people, terrible from their beginning hitherto alike in the favour and indignation of Jehovah, we should esteem it a very great blessing; yet surely they ought to have here one missionary, whose whole soul might be drawn out towards this especial work.

From some communications with a native of Merdin, we find that the custom of avenging murder and requiring blood for blood, exists among the independent Chaldeans and Syrians, and keeps them in continual warfare, where one happens to be killed by the inhabitants of another village. The inhabitants of the village of the person killed, feel it a necessary point of honour to revenge it.

He also mentioned, that the Yezidees were no longer so numerous as formerly, but were greatly diminished by the plague, which happened a few years ago, by which Diarbekr lost 10,000 of its inhabitants.

We had a visit from an Armenian, who was formerly treasurer to Sir Gore Ouseley; while speaking about Christianity, he said, it was no use to speak to the Armenians about it, for they all say, “How can we know any thing about such matters, and that, except as a sect, they are too ignorant to know or care about Christianity.” They are indeed full of the pride of heart that appertains to sectarians, and obstinately resist the Scriptures being translated into the modern languages, because, say they, the ancient language was spoken in Paradise, and will be the language of heaven, and that, therefore, translating the sacred book into that which is modern, is a desecration. How wonderfully does Satan blind men, and how by one contrivance or another does he endeavour to keep God’s word from them, as a real intelligible book, which the Spirit of God makes plain, even to the most unlettered; but the more we discover him endeavouring to pervert God’s word from becoming intelligible, the more we should strive to let every soul have the testimony of God concerning his life in Christ, in a language he understands. In this point of view I look to the schools with comfort.

August 19.—Things here seem most unsettled, and require us to live in very simple faith as to what a day may bring forth. It is stated, that between 20 and 30,000 Arabs are close to the gates of the city. The Pasha has an army about 24 miles from hence; but unable to move, except all together, and there is another regiment under an English officer about 12 miles distant. The deposition of this Pasha seems to be the principal object of these Arabs, in which it is not impossible that they may be fully supported by the Porte. What will be the result of all this we are not careful to know, for we are not to fear their face, nor to be afraid, but the Lord will be to us a hiding place from the storm, when the blast of the terrible ones is as a storm against a wall.

A caravan has just come across the desert from Aleppo, with a guard of 500 men, consisting of 300 camels. Letters brought by a Tartar from Constantinople have all been detained by the Pasha, except a few on mercantile concerns which have been delivered. So many packets sent by Constantinople have been in one way or another detained, that I have no other hope of letters than what my most gracious Lord’s approved love gives me; all which he really desires me to have I shall receive, and more I would desire not to wish for.

We have just heard, that Major T——’s brother, and the gentlemen who left Mousul were pursued by 500 Arabs; but all escaped except a horse of the Capidji,[13] an officer of the Sultan’s, which was laden with money, collected by his master for the government at Constantinople; he could not go fast enough, so he fell into the hands of the Arabs.

The Roman Catholic bishop has received accounts that Algiers is taken by the French, and also some forts in its neighbourhood. Aleppo is quiet, though the Arabs are in the neighbourhood.

Our new Moolah has expressed his surprise at the contents of the New Testament, and wonders how Mohammedans can speak against it as they do. He intends coming to our Armenian schoolmaster on Sundays to read it with him; may the Lord most graciously send down his Spirit upon them, that the one who undertakes to teach what he does not know, may, by discovering his ignorance, be led to the fountain of all wisdom; and may the other learn to love him whose holy, heavenly, and divine name he has blasphemed.

The cholera is much about, but the Lord preserves us all safe.

The Pasha has made up his differences with the Arab tribe, and all the troops have returned, except those under Mr. Littlejohn, which still remain out for fear of an attack before all the harvest is thrashed and brought in.

There are symptoms of great fear on the part of the Pasha, that a struggle is actually going on among those around him for superseding him in his Pashalic, in which they have apparently much probability of success, as the Porte has been greatly injured by his unwillingness to meet her necessities and afford her pecuniary help. Our security, however, is in this, that amidst all, the Lord knoweth them that are his, and will defend them amidst all turmoils and in the most troublous times—in this we find peace and quietness.

The poor men who came to endeavour to obtain from the Pasha here the re-institution of the Syrian patriarch in those churches in Merdin, from which he had been ejected by the Roman Catholic bishop, are now returning without success, but carrying back with them two boxes of Arabic and Syrian New Testaments to the Patriarch. May the Lord water them by his most Holy Spirit, so that they may become the ground of living churches, instead of those of stone which they have lost.

I have been much surprised to learn that all the Arab tribes on these rivers, except the Montefeiks, are Sheahs or followers of Ali, whom I had formerly thought followers of Omar.

I have already mentioned, that on leaving Mousul, Mr. Taylor’s party were attacked and obliged to return to Telaafer,[14] a village between Mousul and Merdin, whence, after having waited for a stronger escort, they proceeded towards Merdin, when the event related in the following letter took place; but the supposed death of the three gentlemen was unfounded. They were only made prisoners and carried to the mountains of Sinjar, among the Yezidees. These people are declared enemies of the Mohammedans, whom they hate; but, on the whole, except when their cupidity is excited, they are not unfriendly towards Christians. They seem, with the Sabeans and some others, such as the Druzes, to be descendants of the believers in the two principles who have blown their pestiferous breath at different times into every system of religion that has prevailed in these countries, corrupting all. However, these Yezidees, be they originally what they may, have now these three gentlemen in custody, and require 7,500 piastres of this place—about £75, for their liberation, and Major T. has sent a person from hence to treat about it.

“My dear Sir,

“It is, I can assure you, with a sincere and melancholy regret at the dreadful, I may say horrible and awful event that I have so lately witnessed, that I sit down now to address a few lines to you. I feel quite unable to give you an entire relation of our misfortunes, and shall content myself with saying, that out of seven as happy people as could well exist on our departure from Mousul, three only have returned. To one so well able to look for consolation, where, I may say, in such an event consolation is alone to be found, fortitude and patience in suffering might well be found. I myself have not attained this, and I may say this event has plunged me in the deepest melancholy. For a relation of facts, I must refer you to Captain Cockrell’s letter to Major Taylor: we were attacked and compelled to fly, and in the confusion, Mr. Taylor, his servant, Mr. Bywater, and our companion, Mr. Aspinal, were murdered. We, that is Captain Cockrell, Mr. Elliot, and myself escaped, though I was, I believe, especially fired at, as on descending the hill four or five whistled close past me. That we were betrayed, and moreover, our companions assassinated by our own party, no doubt exists in my mind. All that were killed out of 500 people that were with us were these four. They again, out of all, happened to be the only ones among us who carried money. We have done every thing in our power to recover their bodies but without effect: on our return to Telaafer, after having been twenty-six hours on horseback in the desert, we wrote a note, in the hope that they might be prisoners at Sinjar, and offered 4,000 piastres for them if they were brought in safe. The Kapidgi Bashi left for Merdin before we could hear of our messenger; he returned after three days, and said he had seen their clothes and pistols, and that they were all murdered. Mr. Taylor he mentioned as having been run through the body with a spear. This was one out of many reports of a similar nature, and we were fain to give them up for dead. (They could not possibly have been alive had they escaped, as there was no water within twenty-four hours.) All our things were pillaged. I lost all my papers, including your letters, and all that was left were a few pairs of white trowsers. This was most assuredly done by our own party; even our own baggage man, before my eyes, almost laid hold of my turban and pistol, which I had laid upon the ground, and on my laying hold on him, actually drew his dagger. I never witnessed such villany in my life. All our guards were laughing, as if nothing had occurred; and, although I may be wrong, yet I do venture it as my opinion, that there were no thieves at all, but that it was treachery altogether. You will be surprised to hear that Captain Cockrell and myself start to-morrow on the same road as before. I trust in God alone for protection, as we have no guards at all. If I ever reach Exeter I shall not fail to call on Miss Groves; but after what has happened who can say, “He shall do this.”

“We take no baggage of any description, being fully aware of the danger and impracticability of so doing; so that if we are again attacked, we shall be able to gallop for our lives. Now, adieu, my dear Sir. I will write from Constantinople if I reach it; in the mean time excuse this hurried scrawl, and believe me, ever

“Yours very sincerely,

“W. Hull.”

“Mr. A. N. Groves.”

In consequence of the receipt of this intelligence, Major T. sent off Aga Menas to Mousul, to treat about the liberation of the captives, and we are anxiously waiting the result.

My dear brother Pfander and myself having come to the conclusion, that with so large a school, and so many objects of one kind and the other as there are here requiring attention, it would be impossible for me to leave this and go with him into the mountains; this led to the further determination on his part to return to Shushee next year, having first spent a few months at Ispahan, to complete his knowledge of Persian; and I of course was prepared to be left quite alone, but still my heart was fully sustained with the confident hope that the Lord would not only do what was right, but exceedingly abundant above all I could ask. On all sides nothing but silence prevailed:—three packets of letters had been lost between Constantinople and this, and one between Tabreez and this, and all the letters from India had been detained, by the Arabs on the river being at war with the Pasha for four or five months. Therefore I knew nothing of the movements of any of my dear friends, and all was left to conjecture; sometimes, when faith was in full exercise, I felt assured that the Lord was doing all well; at others, I hardly knew what to think. I had written to my very dear friends in Petersburgh, Dr. W. and Miss K. to come if possible and as soon as possible; but their having left Petersburgh doubtless prevented their receiving my letter. From my dear friends in England I heard little; from Ireland not a word. Things were in this state, when suddenly there came in three Tartars bringing us three packets, so full of Christian love, sympathy, and such good tidings, that it almost overcame our hearts, weak from long abstinence from similar entertainment, and even on this day, the third from their arrival, they fill my heart till it runs over. To hear and see that those one most loves, are indeed joying and rejoicing in their holy, most holy relation to God in Christ,—the relationship of sons and daughters, to see them anxious to walk blameless in all the ordinances their Lord has left them, while they glory in being free from the law of condemnation, and desire to know no freedom from the law of loving obedience: moreover, to see them becoming more and more sensible to the great truth that inestimable as knowledge is, it is what devils may share, but that the love of Jesus, and a tenderness of conscience as to his will, is infinitely higher than that, and that therefore his high command to the members of his church to love one another as he loves them, can never be slighted by them:—oh, to see this it does indeed rejoice my heart, and I pray among us all that it may abound more and more, particularly among us who have been so graciously and so kindly led into all the holy freedom of the Gospel. Let us see we use it not as a cloak of maliciousness, but as the servants of Christ, loving and serving one another, not returning evil for evil, or reviling for reviling, but contrariwise blessing. The path God’s children have to take when they are determined in the name of the Lord not to give the name of God’s truth to any thing merely human, knowing that it is a vain thing to teach for doctrines the commandments of men, is so naturally offensive, that our zeal for the truth should lead us to pray for such especial graces of the Spirit as may prevent any unloveliness in our walk, preventing the Lord’s dear children from coming, and seeing, and drinking of that well-spring in Christ by which we have been so refreshed and invigorated. Whilst we profess, my very dear friends, absolute freedom from man’s control in the things relating to God, we only acknowledge in a tenfold degree the absoluteness of our subjection to the whole mind and will of Christ in all things. As he is our life hid with him in God, so let him be our way and our truth, both in doctrine and conversation. How many, from neglect of this lovely union, have almost forgotten to care about adorning the doctrine of God their Saviour in all things. Let us, my dear brethren and sisters, pray that we may be united in all the will of Christ. This is a basis not for time only but for eternity, and for that glorious day especially, when the Lord shall come to be glorified in all his saints, and admired in all them that believe. But not only did my packets bring me joyful tidings of the Lord’s doings among those whom I especially know and love, but they also brought me intelligence that he had prepared for me help from among those who had been known and approved, and whom I especially loved. How I felt reproved for every doubt; and indeed the Lord so fully has let his goodness pass before me, that I am overwhelmed, and feel I can only lay my hand upon my mouth, and whilst overwhelmed with my own vileness and unworthiness of the least of all my most gracious Lord’s loving kindnesses to me, yet glory in that dispensation of grace which ministers to us, not according to our deserts, but the unbought, unbounded love of God. My letters tell me that my very dear brethren and friends, Mr. P., Mr. C., his sister, and mother, and little babe, and Mr. N., are coming to join us, with possibly a fourth. Now this does seem altogether wonderful, and whilst not at all more than I ought to have expected, yet more than I had faith to expect. Yet while I have nothing to say for myself, I desire to say all for God: it is like him, all whose ways are wonderful, and, towards his church, full of mercy, goodness, and truth. Oh, how happy shall we be to await the Lord’s coming on the banks of these rivers, which have been the scene of all the sacred history of the old church of God, and destined still, I believe, to be the scene of doings of yet future and deeper interest at the coming of the Lord; and whilst I should not hesitate to go to the furthest corner of the habitable earth, were my dear Lord to send me, yet I feel much pleasure in having my post appointed here, though the most unsettled and insecure country beneath the sun perhaps. In every direction, without are lawless robbers, and within unprincipled extortioners; but it is in the midst of these, that the Almighty arm of our Father delights to display his preserving mercy, and while the flesh would shrink, the spirit desires to wing its way to the very foremost ranks of danger in the battles of the Lord. Oh that we may more and more press on this sluggish, timid, earthly constitution, that is always wanting its native ease among the delights of an earthly happiness. Oh, may my very loving, zealous brethren, stir up my timid, languid spirit to the mild yet life-renouncing love of my dear Lord, which, whilst it was silent, was as strong, yea, stronger than death.

My dear friend and brother P—— and his wife have been baptized too; to see this conformity to Christ’s mind, is very delightful; and how wonderful, too;—so strong a current of prejudice is there against this simple, intelligible, and blessed ordinance. I learn also, that he and my dear friend the A——[15] are preaching the everlasting Gospel themselves, and with some others of those we love, employing others to preach it. This also is good news.

September 10.—No accounts have been received from Sinjar regarding our travellers. I fear this is ominous, for if ransom is what the Yezidees want, would they not have contrived to forward some notice to Bagdad? however, a few days will most likely disclose the truth, as on the 8th Meenas reached Mousul.

We have just heard that the Nabob of Lucknow’s brother, on his return from a pilgrimage to Mished, was taken prisoner with the whole caravan by the Turcomans. This amiable Mohammedan came from India on a round of pilgrimages. He has visited Mecca and Kerbala, and was now returning again to this place on his way home to Lucknow, after which he purposed returning again, and going through Persia, Russia, Germany, &c. to England. He was robbed once before between this and Aleppo.

The Pasha has just sent to the Factory to say, that the cholera has extended its ravages to Kerkook, and to ask for advice, and what is to be done should it reach this place with its epidemic violence. Mr. M—— is going therefore to write directions, and Major T—— will get them translated into Arabic, for the use of the people here. Blessed be the Lord’s holy name, our charter runs, that in the pestilence, “though ten thousand fall at thy right hand, it shall not come nigh thee;” on this, therefore, we repose our hearts. The Pasha seems perplexed to know, in the event of its reaching Bagdad, where he shall go with his family for safety. It is certainly an awful thing to look at Tabreez, where they say, that 8,000 or 9,000 have died out of 60,000; and two years ago at Bussorah, 1,500 out of 6,000, so that the houses were left desolate, and the boats were floating up and down the creek without owners, and when persons died in a house, the rest went away, and left the bodies there locked up. But we have in our dwellings a light in these days that they know nothing of, who know not our God either in his power or his love, so that the heart is enabled to cast all, even the dearest to it, on the exceeding abundance of his mercy.

September 10.—I fear the intelligence we have just received of poor Mr. J. Taylor, Mr. Bywater, and Mr. Aspinal, and the Maltese servant, leaves us little room to hope but that they have all been treacherously murdered. Our Moolah tells us, he received a letter from a friend of his at Merdin, stating, that they were murdered—not by the Yezidees at all, but by the party of Arabs sent by the Pasha of Mousul to protect them, in conjunction with a party from Telaafer, an Arab village, where they spent a night. It appears, that when the attack was made, Mr. Elliot, Captain Cockrell, and Mr. Hull galloped off after being stripped; but Mr. Taylor, Mr. Aspinal, and Mr. Bywater got entangled among these robbers, and Mr. A. shot one of the Arabs with his pistol; and afterwards Mr. B. shot another. It then became with these lawless plunderers, no longer a matter of simple robbery, but of revenge and death. They killed these two young men, and then pulling Mr. Taylor from his horse, killed him. I confess, when I saw them mounting their horses, strongly covered with offensive weapons of warfare, I felt very little comfort about them, for, if they were attacked, it would only be with an overwhelming force, or they would be given up in treachery, in both which cases almost all the danger arises from resistance. Those wretched plunderers seek not life, but booty; this quietly yielded, you may go; but if you use the sword, you perish by the sword. If you carry money, or any thing valuable, you are exposed to be stripped, and if you go armed, to be killed. About three years ago, the French interpreter was going the very same route, and near Telaafer he was attacked, and stripped; but they let him go free. The fate of these gentlemen has greatly affected us all. A delay must now take place in the steamboat communication, for it is not probable that this route can ever be so disregarded, but that some effort, sooner or later, will be made. Let our impatient hearts hush their murmurings; it is the work of a loving Father, who declares to his children, that all things shall work together for their good; yea, the disappointment of present hopes shall, by heavenly patience, yield the peaceable fruits of righteousness to those who are exercised thereby.

September 14.—We have just heard, that an order has been given out in one of the mosques, that the Mohammedans shall receive no printed books. Whether this watchfulness is the result of Mr. Pfander having employed a man, a Jew, to sell Bibles, Testaments, and Psalters, or whether, at the suggestion from the R—— C—— B——, I know not. How near the principles are of the beast and the false prophet—how easily they harmonize and help each other!

We have lately heard some interesting details of the numbers of the Jews in the places north-east of Persia. A Jew who has travelled in these countries states, that there are,

| In. | Language spoken. | Families. |

| Samarcand | Turkish | 500 |

| Bokhaura | Turkish and Persian | 5,000 |

| Mished | Turkish and Persian | 10,000 |

| Heerat | Turkish and Persian | 8,000 |

| Caubul | {Pashtoo, but Persian} | 300 |

| Bulkh-(Caubul) | { generally understood} | 300 |

There are also in the villages about some Jews, from 20 to 100 families. Their knowledge of the Hebrew is very confined; very few understand it at all; they have also very little knowledge of the Talmud. We hope from time to time to collect more particulars to correct, confirm, or cancel these, and all other accounts of a similar nature, for in these countries it is not one account that can stand, and when confronted by 50 more, it can still be only considered as an approximation to truth.

September 16.—Our long expected packet by Shushee and Tabreez has just arrived. The messenger, on reaching Kourdistan, found it in such a state of danger and confusion, that he was afraid to proceed, but went back again, and came by a longer but more quiet way. Another cause of delay seems to have been their going to India, and back again to Tabreez. The information contained in this packet is most interesting. From Petersburgh we heard from several friends, all encouraging, comforting, and rejoicing us. The Lord seems to give them courage still to persevere; and dear sister —— intends, after recruiting a little in England, to return again to her work there. I feel satisfied it is a most interesting field, and that ere long in Russia some tremendous changes will take place. The poor are anxious for the word of God, and the nobility despising the hierarchy, and, therefore, that blind priestly domination under which it has groaned, will finally fall to pieces; infidelity will take openly its side, and the Lord’s saints theirs.

Dear Mr. K—— tells us, that some dear American brother, by name Lewis, has sent him money to procure for his family a house in the country during the few months of a Russian summer. How loving and bountiful a Lord ours is, supplying his most affectionate and waiting servant with all he needs; it makes every little bounty so sweet when it comes from a Father through one of his vessels of mercy. Oh, who would not live a life of faith in preference to one of daily, hourly satiety—I mean as to earthly things; how very many instances of happiness should we have been deprived of, had we not trusted to, and left it to his love to fill us with good things as he pleased, and to spread our table as he has done, year after year, and will do, even here in this wilderness.

From Shushee we have also heard, that our dear brother Z—— and an Armenian had been travelling and selling Bibles and Testaments. They went first to Teflis; from thence to Erzeroum, Erivan, Ech-Miazin, and back again to Shushee. What success he had in selling Bibles and Testaments we do not know, but at Erzeroum, he was accused by the Mohammedans before the Russian authorities, but let go. He returned home in safety under the hand of the Lord. There is also in the letters of our brethren most pleasing accounts of a young Armenian, the son-in-law of the richest Armenian merchant in Baku, supposed to be worth half a million. This young man, at a visit of Z—— and P——, was much interested by their conversation about the New Testament, and they went away, leaving him an interesting inquirer. He, however, still pursued his way alone, and attained a perfect understanding of the Armenian Testament, which at first he was able to read but indifferently. He then felt himself unable to proceed in mercantile transactions as before; so that his father-in-law told him, that much as he regretted separating from him, if he became so pious, they must part. Well, he said, he could not give up his convictions, and he was sure his Lord would not allow him to want; so he left his father-in-law, and learnt the trade of a taylor. From the very first he began to teach his wife, and she takes part with him; and he is now selling Bibles and Testaments, and circulating tracts among the Russian soldiers. This is a sight indeed! for centuries perhaps they have not seen one of their own body rising up, and choosing to suffer affliction with the people of God, rather than enjoy the pleasures of sin for a season; and the sight is as strange to Mohammedans as to Christians. May the Lord sustain, comfort, and bless him out of his heavenly treasures.

From Tabreez our tidings are heavy, or rather would be, but that the Lord of love directs and orders all, and sees the end from the beginning, yet they have also good tidings too. I have already mentioned, that the cholera had been raging at Tabreez; but we learn, that not only this, but the plague is there also, to a most frightful extent. I will just copy here the account our dear sister Mrs. —— has given us; and for whose safety we desire to bless the Lord; she says,

“Before this reaches you, you may have heard of the sorrow and desolation that have befallen this city within these last two months. Thousands around us have been cut off by the cholera and the plague. The former raged so furiously for the first month, that 2 or 300 died daily. Symptoms of the plague first were discovered in the ark among the Russian soldiers, which manifested itself by breaking out over the body in large boils; the person attacked, feeling himself overcome by stupor; many died before it was thought what it was; precautions were taken, and they were sent out to camp at some distance from the town. The disorder has not raged among them so much as it has in the town. I cannot tell you how great the fear was that was struck into the minds of the people. Many were taken ill through fear, of which they died. Previous to the city being quite deserted, men, women, children, of all denominations, collected themselves together in large bodies, crying and beseeching God to turn away his judgments from them: this they did bareheaded and without shoes, humbling themselves, they said, because they knew they were great sinners. The air resounded with their cries day and night, particularly the latter, and often during the whole of it. Oh, did they but know the truth as it is in Jesus. At length all classes fled to the mountains, leaving the town quite deserted. Alexander told me, on his return one day from the city, that he had not met a person. All the shops in the bazaar were forsaken, so that from this you may derive some idea of the terror that has possessed this people.”